Review of 'MONU #36: New Social Urbanism'

Optimism About the Future of Urbanism

Nishi Shah

13. February 2024

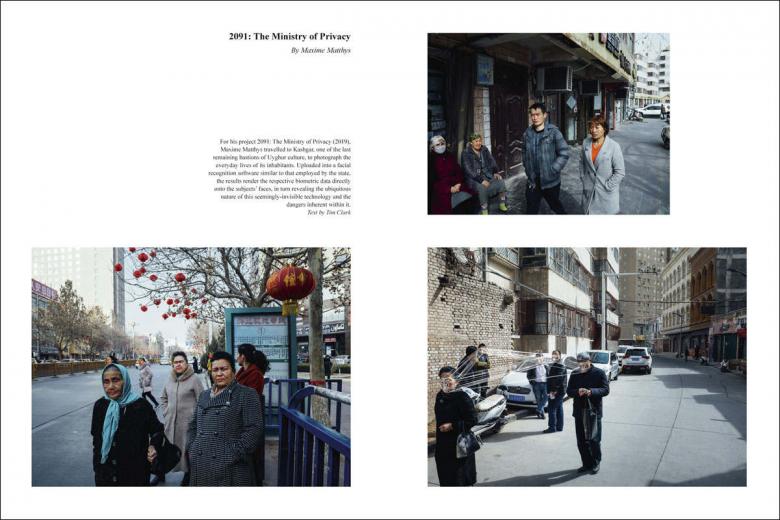

Maxime Matthys's image on the cover of MONU #36: New Social Urbanism captures the emergence of an omnipresent techno-centric urban future.

The latest issue of MONU, the magazine on urbanism put out by BOARD in Rotterdam, explores the phenomenon of a “new social urbanism.” What is it, and how does it relate to other “urbanisms”? Architect and writer Nishi Shah digs into MONU #36: New Social Urbanism to parse the theme.

Ever since the genesis of city planning, the concept of “social urbanism” has permeated the lexicon of architects and planners as a means of prioritizing social interactions on par with those achieved through spontaneous urban growth. Despite the impression that planning fosters social connections, social urbanism is a deliberate effort that addresses the deficiencies of planning, especially modernist planning. The pandemic recently thrust “new” urbanism into the limelight, highlighting the sheer mess, fractured deficits, and anti-sociability inherent within the spatial designs resulting from consciously planned urbanism. The 36th issue of BOARD's now annual journal, MONU (Magazine on Urbanism), accentuates the imperative for a nuanced comprehension of a “new social urbanism.” This edition resonates with prior issues, notably #35: Unfinished Urbanism (2022) and #33: Pandemic Urbanism (2020). These issues explored themes such as unpredictable transactions and enormous economic inequity amid the pandemic. Expanding on those issues, New Social Urbanism demands that a broader perspective of understanding is required: transcending the conventional ‘social’ definitions and grappling with the multifaceted conflicts faced in a post-pandemic, rapidly digitizing society to reconceptualize the foundational tenets of ‘sociability.’

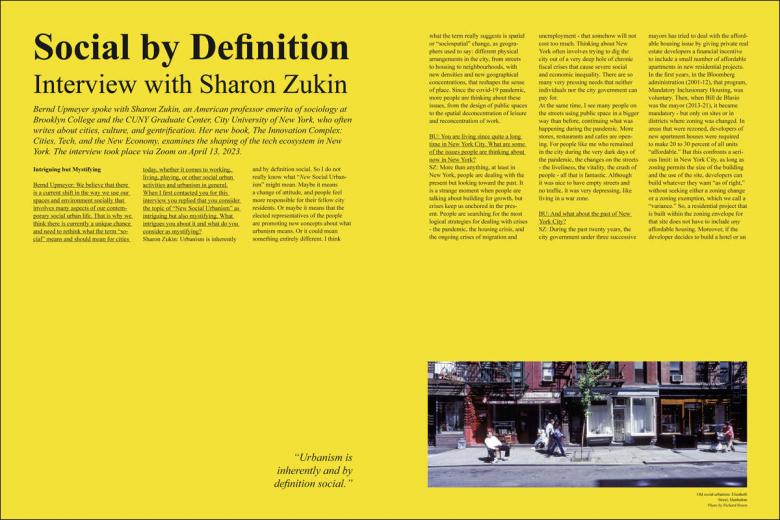

Sociologist Sharon Zukin, in an interview with MONU editor in chief Bernd Upmeyer, is rather pessimistic about whether a “new social urbanism” is rising.

MONU #36 endeavors to address a harmonious equilibrium between the public and private realms, real and virtual worlds, and collective versus governmental responsibilities; to foster inclusive sociability within radically different urban structures. The issue, rich with interviews, articles, photographs, and essays by experts operating at the nexus of urbanism and social science, spans global contexts, from the bustling megacities of New York City and Hong Kong to the localized perspectives of Valencia and Librino. Though featuring twenty distinct contributions, the issue coherently articulates overarching themes on “new social urbanism”: the ramifications of Covid-19, evolving urban strategies, the rise of communal spaces, and the evolution towards immersive cities.

Table of Contents of MONU #36: New Social Urbanism.

An in-depth examination of the root causes of resource exploitation and the contemporary missteps of urbanism unfolds in this issue. In her essay, Tatjana Schneider foregrounds structures of unsustainability, “gas-guzzling” infrastructure, climate crisis, and critical global analysis. Similarly, Paul Kalbfleisch dissects the implications of zoning laws and a car-centric culture, highlighting social segregation and the eventual 2020 “social recession.” This pervasive lack of human interaction and social coldness has become particularly pronounced in New York City where socio-economic disparities — aggravated by the pandemic — exacerbate challenges in managing extreme density with little to no affordable and hygienic housing, as explained by Richard Plunz and Andrés Álvarez-Dávila in their contribution, as well as in MONU editor Bernd Upmeyer's interview with Sharon Zukin. Urban oddities manifest more starkly in cities where planning mistakes have rendered ghost towns, as in Agnes Katharina Müller's portrayal of San Francisco, or ordered public neighborhoods that paradoxically reveal the absence of livability, as detailed by Constanze Wolfgring.

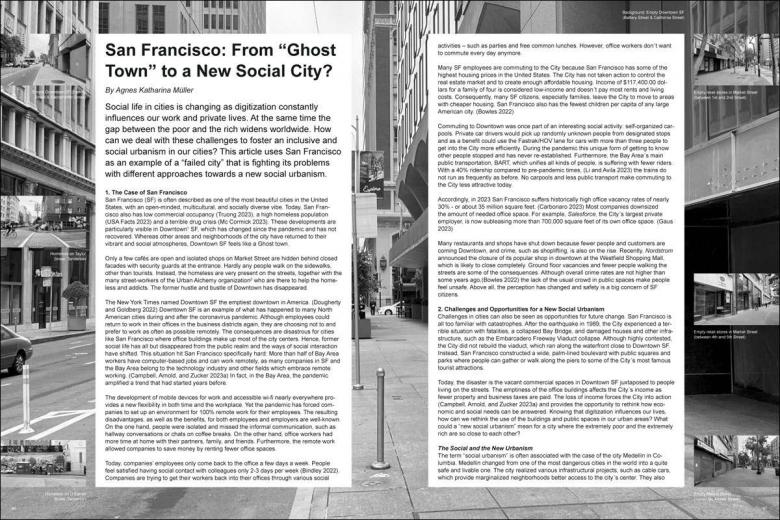

In the wake of San Francisco’s post-pandemic shift into a ghost town, Agnes Katharina Müllerthis's “San Francisco: From ‘Ghost Town’ to a New Social City?” examines inclusive strategies, aiming to revitalize the city’s downtown into a vibrant “social hub.”

Yet, amidst these looming challenges, MONU #36 illuminates pathways of redeeming neighborhoods by emphasizing innovative housing and urban policies as catalysts for social revitalization. While not entirely groundbreaking, these policies employ straightforward yet impactful social space-making approaches ranging from citywide initiatives to individual housing units, addressing the intersections of work, private life, public engagement, and communal activities for all inhabitants. From Paul Kalbfleisch's advocacy of prioritizing joy through playgrounds for the human spirit to Valentina Rizzi's transformative reappropriation through performative arts, of embracing “marginalized spaces as generative grounds for collective reclamation,” the issue offers tangible solutions to restore a sense of neighborhood familiarity and rejuvenate public spaces as traditional arenas for social interaction. Brian Holland's piece on “piggybacking” discusses a space-sharing practice that posits marginal activities alongside popular developments to form multi-use structures. This strategy challenges the disconnectedness and homogeneity often associated with modernist planning while fostering a vision of diverse, resilient collectivity. Several articles within the issue resonate with the central theme of collectivity by suggesting refined real estate policies, advocating for collective ownership, emphasizing the right to the city, adopting the city as a commons, and exploring social capital. These discussions suggest that prioritizing social design, placemaking, and communal sharing of urban resources — rather than solely focusing on privatization and commercialization — will inherently lead to financial gains and environmental consciousness facilitated by increased public engagement and action.

In “2091: The Ministry of Privacy,” Maxime Matthys's photographs of people in Kashgar run through facial recognition software illustrate what a merger of body, technology, and surrounding structures might look like.

Most importantly, many of the contributors to MONU #36 confront the predominant and inevitable shift towards post-public, digitally-immersed, tetra-dimensional cities. The magazine's cover unequivocally underscores how envisioning “new social urbanism” for the 21st century necessitates acknowledging and naturalizing this densely layered digital urban environment. Maxime Matthys's cover photograph, sourced from his project “2091: The Ministry of Privacy,” compellingly unveils the omnipresent yet often invisible technology that overlays our urban experiences. Tatjana Crossley references the insights of contemporary philosopher David Chalmers, who asserts that “virtual reality is genuine reality,” especially given how augmented reality has manifested itself in alternative urbanities through video games, art exhibitions, and advertising. We're on the cusp of “techno-social transformations,” according to Francisco Silva, while Serafina Amoroso suggests that, by equipping our houses and cities with digital screens, AR technologies, and hybrid spaces, architecture’s integration of virtual realms is moving space toward a “tetra-dimensional urbanism.” As physical presence is no longer a prerequisite, and as social interactions are distilled to their core essences of connection, emotion, and communication, the multiplying spectrum of socializing by merging realities heralds a promising horizon for architects, planners, and social scientists. Design now transcends traditional physical territories, ushering in a new era of four-dimensional social landscapes in a merging of body, technology, and structures.

Architect Izaskun Chinchilla, in another interview with Upmeyer, believes we are heading toward a hybrid situation in which we will socialize both physically and digitally, multiplying the spectrum of the ways of meeting and socializing.

Being a reader from an Asian nation where social interdependence has historically influenced architectural ethos, the global implications of this theme captivate my attention. Yet, upon reflection, the limited analysis from the Eastern perspectives stands out, especially considering the region's rich tapestry of interconnected atmospheres, collective harmony, familial ties, and stronger social bonds. It would be particularly enlightening to explore the implications of social distancing in these inherently communal societies and contemplate the potential manifestations of “new social urbanism” within such unique and dense cultural landscapes. Nevertheless, this latest issue of MONU, with its signature aesthetic format where each contribution has a unique layout, deserves superlatives for its wealth of ideas. It stands as a compelling read, initiating vital dialogues on the power of sociability and livability of cities, envisioning cities as socio-technological ecosystems, and undoubtedly eliciting optimistic trajectories for the future of urbanism.

MONU #36: New Social Urbanism

Edited by Bernd Upmeyer

128 Pages

Paperback

BOARD Publishers

Purchase this book

Browse the issue on YouTube:

Nishi Shah is an Indian architect, co-curator for Archis's newsletter, and a writer currently based in the Netherlands. With a strong inclination towards research and critical thinking, her interests foster interdisciplinary dialogues within the design discourse.